It's suspenseful all right. Will Philip Massinger's neglected Jacobean tragedy,

The Unnatural Combat,

survive a script-in-hand performance in Gray's Inn Hall? And will the pro-am

cast - the Bar v. Shakespeare's Globe - be oil and water?

This is part of Globe Education's commendable Read Not Dead project, dedicated to resuscitation.

She's absent, but I have her

figure here;

And every grace and rarity

about her

Are by the pencil of my

memory

In living colours painted on

my heart.

Malefort, an ambivalent war hero dragged out of jail for his first scene, is racked with desire for the beautiful Theocrine - his daughter, ew. He kills his equally ambivalent son and the wheels of retribution grind away.

I don't guess all the lawyers/actors correctly, which is instructive. Sir Michael Burton QC and Colin Manning have a forensic

élan. Emily Barber, who was a touching Innogen in

Cymbeline at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, plays Theocrine with doomed delicacy; Tok Stephen deals well with the ambiguity of her half-brother; Tim Frances takes command of the hall, explores the light and shade of Malefort and builds an intimate connection with the audience. The play's director Philip Bird dips in and out, taking miscellaneous parts.

The only run-through happened this morning.

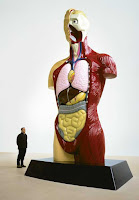

It's a tale of cynical politics and betrayal, and there's speculation that Malefort was based on George Villiers, 1st Duke of

Buckingham (1592-1628), the royal favourite who was assassinated after his popularity waned. Here he is, probably as Lord High

Admiral, painted by Daniel Mytens the Elder (National Maritime Museum).

This performance is a counterpoint to last week's appeal in the UK Supreme Court about abortion law in Northern Ireland, which addressed rape and incest. With no jury present, counsel knew better than to try to stir emotion. Their approach can be studied on the court's website. This afternoon the play-reading lawyers have to tackle an emotional open runway. There is a sympathetic audience and plenty

of room to move in the round, with clothes mainly their own and hardly any props.

After a court hearing it might be interesting to cast a play with the same line-up.

King Lear for

Miller, the Brexit Article 50 appeal, with Lord Pannick QC and James Eadie QC splitting the title role and Gina Miller as Cordelia.

Throughout this afternoon's performance the Director of Globe Education, Patrick Spottiswoode, has been willing everyone on like a parent. He has a battered book with him. It's a source for next year's commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the abolition of theatre censorship in the UK ('the Lord Chamberlain regrets...').

Like me, he went to the 1968 London production of

Hair, its first beneficiary. I saw the watered-down London revival a few years ago and felt it was a period piece misunderstood by the cast. How times change. But time is the key to this afternoon's shared mystery. This is not about taking something out of the freezer, but celebrating a continuous river. It's an important process.