|

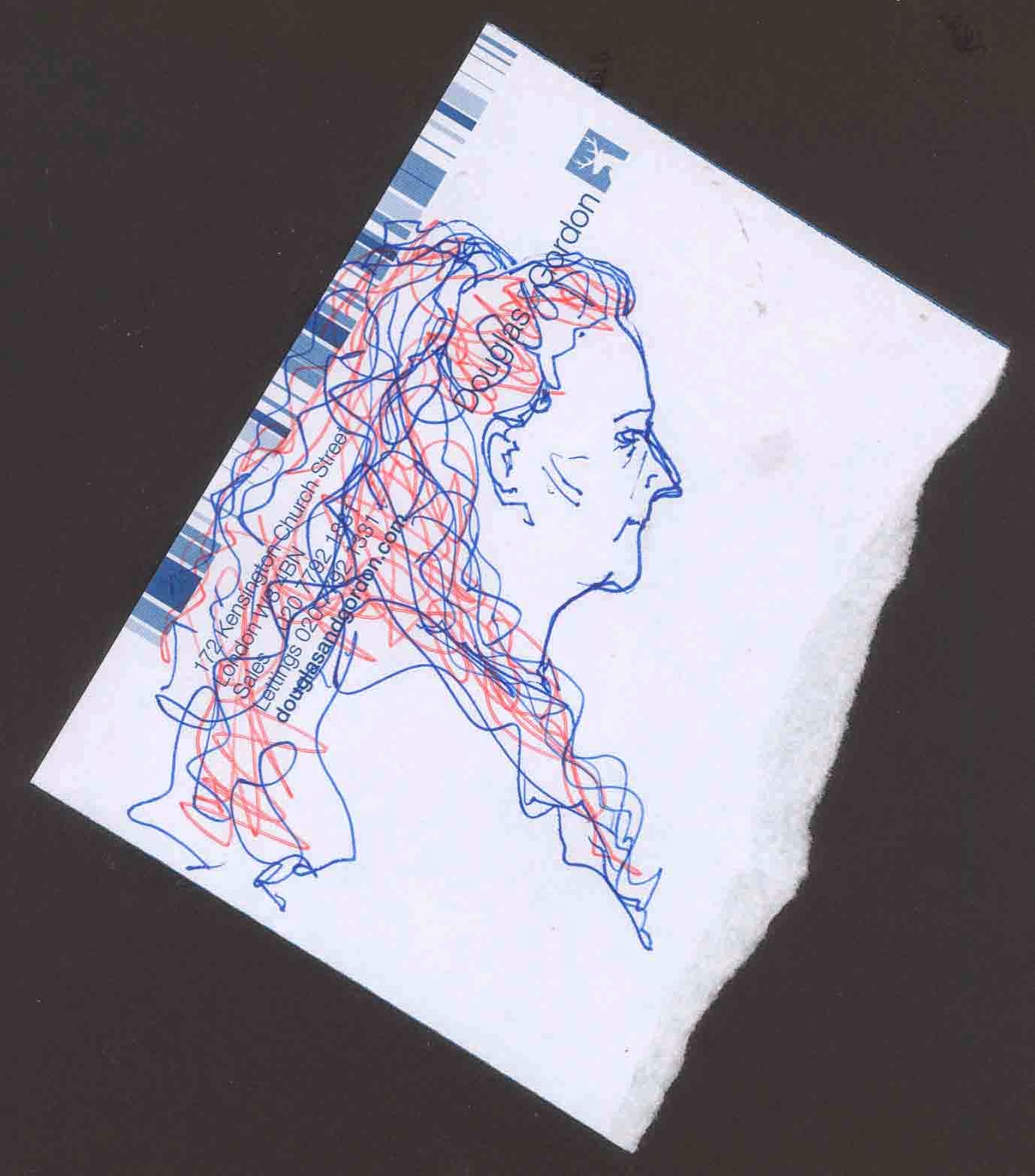

| Outside the court |

It is illegal to draw here. Proper court artists do it from memory.

So what does an improper non-court 'artist' with no trained memory do?

David Spens QC, cross-examining Andy Coulson, refers to a news editor talking about trying to pinpoint the Lotto rapist by triangulation (based on the locations of his phone signals).

Coulson seems indignant at the use of a long word and says he'd have remembered it. 'If anyone had used a phrase [sic] like triangulation I would have been incredulous.'

I know what triangulation means (stupefying as that might be to Mr Coulson) but here in court I lack the wherewithal to do it.

I could still get a more accurate drawing, however, if I split the scene mentally into triangles and write a description (top right of counsel's wig, tip of sword, bridge of defendant's nose, 40°, 90°, 50°).

I'm too distracted to do that, so I have to rely on memory. And, to echo something which is said in the witness box a lot today, I don't remember. I don't see the point of drawing from memory (and I'm far too posh to draw from photos) but I haven't reached the important stage of creating something new from memory.

Meanwhile, casual scribbles seem to be the most reliable way of tapping into blurred memory.

When the day's hearing is over, I go to life class. Before kick-off I ask the model to pose briefly in one of Rebekah Brooks's default attitudes.

|

| Life-class model in Rebekah Brooks's pose |

The aura around Rebekah Brooks reminds me of two pre-Raphaelite images:

|

| 'Hope', Edward Burne-Jones |

|

| 'Hope', George Frederic Watts |